During the transition period, Romania went through several demographic transformations. The intense urbanization of the communist period had taken the urban population from about 20% in the 1940s to more than 50%. After the Capital, 7 major regional development poles had appeared: Timișoara, Cluj, Brașov, Craiova, Iasi, Galați and Constanța.

Each had a regional CFR and a comprehensive university, but also populations of more than 300,000 inhabitants, according to a report by the group Rethink Romania. In the regions, especially the residences of the county gained momentum, another 20 that have populations of more than 100,000 inhabitants. But the great wave of urbanization was reversed with the failure of communist industry. In the 90s, there was talk in many cases of a re-ruralization: both authentic (the return of some workers to their countries of origin) and administrative (suburbanization).

What are the most dynamic cities in Romania?

To map the emergence of these new demographic and economic poles, Rethink has developed an index based on the identification of the main economic and demographic trends using a basket of high-confidence proxy data. Such data includes housing construction, the attraction of students from outside the county, the number of jobs, etc. Although it has allowed us to identify the meaning of the demographic evolution, the dynamism of the development poles is influenced by many other factors that can influence, for example, the business environment or the quality of life. Many factors are extrinsic and others are difficult to measure.

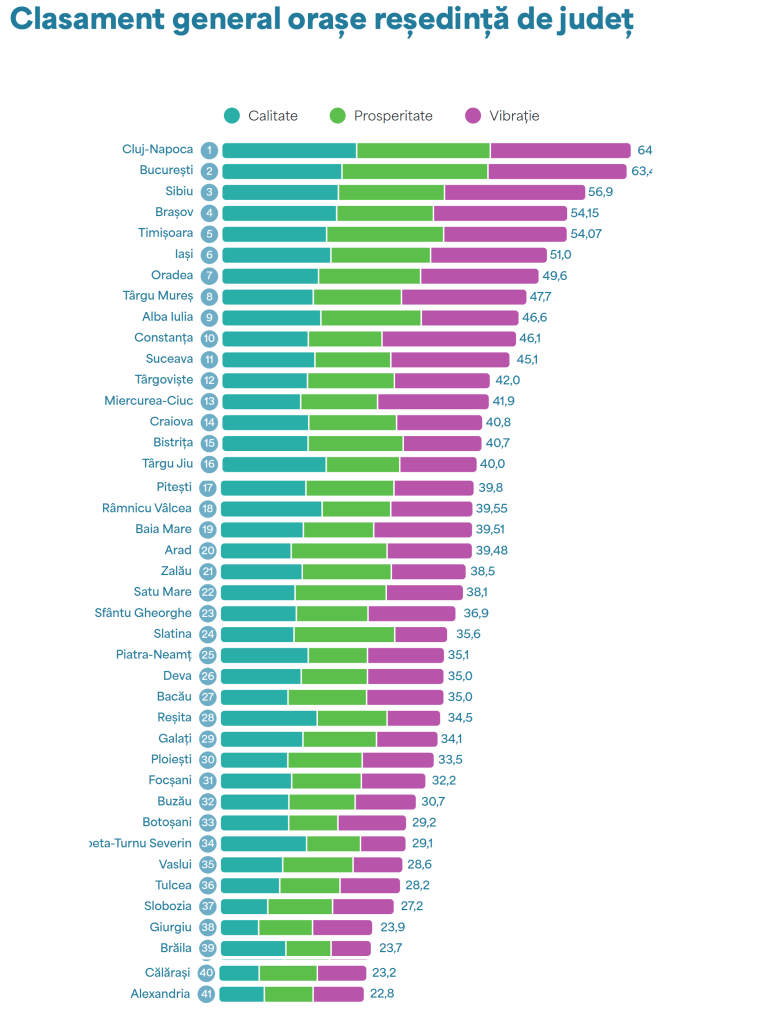

Recently, the Institute for Visionary Cities (IOV) launched a extensive index which rates Romania’s main cities (Bucharest and county seats) based on 51 criteria. These are grouped into 13 domains, in turn amalgamated into 3 major categories (quality, prosperity, vibration). The 51 criteria, weighted accordingly, include both demographic and economic aspects as well as many other sets of data: from geographic data (climate, access to green space) to civic elements (local associative environment) to many economic or cultural aspects.

The index not only measures the quality of local administration, but also the impact of the private environment or the geographical position of each individual city. This aspect is important as access to historical infrastructure or a better climate can be important factors in the puzzle that determines the success and attractiveness of a city.

Although the methodology and objectives of the Rethink and IOV studies are different, the results obtained show many similarities.

In particular, Rethink had identified six major development poles with demographic resilience: Bucharest, Cluj, Timișoara, Iași, Brașov and Sibiu. These poles were also placed in the first 6 positions in the general hierarchy resulting from the City Index developed by IOV.

At the same time, IOV emphasized the existence of numerous points of excellence in the case of individual cities. For example, Vâlcea (county) stands out for its high life expectancy, while Miercurea Ciuc has a dynamic associative environment and Reșita is good at attracting European funds.

Crucially, the study scales the performance of cities analyzed by population, which minimizes – but does not completely eliminate – the advantages of large cities. Obviously, some benefits of a larger population (the existence of a university, a large number of transport connections, diversified services) will not be eliminated by the use of relative data (to the population of the county).

The need to be attractive

After 2029, most of the withdrawal of the “decrees”. The accelerated aging of the population (and the decline of the working-age population) has already affected many European or East Asian countries, resulting in an asymmetric decrease in the population, says the Rethink report.

Contrary to the expectation that housing will become cheaper or that the pressure on the big cities will decrease, the phenomenon of population concentration has accelerated in many cases. Young people leave from the oldest cities, often taking the route of a few attractive magnetic cities. These are not necessarily the biggest. For example, in Spain, fast-growing cities include the capital Madrid, but also regional cities such as Valencia or Alicante. In the United States, the rise in popularity of “remote” work and rising housing prices in big cities have led to unexpected booms in relatively small towns like Coeur d’Alene, Idaho , or Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

In the future, we expect that in Romania a limited number of magnetic cities will attract the majority of immigrants from the domestic and international level. In this regard, there will be a particularly high pressure on the country’s cities to “perform”. This provision can take the form of successful specialization (for example in a sector of industries or type of services) or of providing a high standard of living at several levels.

The pressure to be an attractive place, like a city, is increasing. After 2030, demographic trends make the attractiveness of cities an important asset in what will be a zero-sum game: high-performing cities will often grow at the expense of those that do not offer adequate economic prospects or a desirable lifestyle for the highly skilled. the young people.

The trend of demographic concentration in some poles is already visible. The best example is the southern part of Romania, where the capital has had a positive trajectory, but most cities have faced a sharp decline during the transition. Transylvania, on the other hand, stands out for its polycentric nature of development.

Conclusion: cities must be attractive to prevent a sharp decline in population and taxpayers.

There is growing evidence that shows that the economic boom of the last 20 years translated differently for Romanian cities. Some of them have taken advantage and strengthened their position in the national economy, have become attractive and have managed to offer a diverse range of services to citizens. Others have taken advantage of the natural advantages they have, for example the proximity of the western border or the great communication routes.

At the same time, in the background of an imminent acceleration of the aging process of the population, cities must be attractive to prevent a sharp decrease in the population and the number of taxpayers. It has already been observed in other states that the demographic decline accentuates the asymmetries of the demographic evolution between the cities. On the other hand, since the relative development of cities seems to be at least partially conditioned by a large population, there is a risk that the less attractive municipalities will face a decline in the supply of public and private services and implicitly with the training of a vicious circle of decline.

However, the economic growth in Romania in the last 24 years provides most of the cities with resources that – together with the creativity of the business environment and the authorities – give them the opportunity to reinvent and improve it in a way that guarantees its relevance. in the following decades.